Our bodies are always changing. Having good data about how we are changing can help us make appropriate adjustments to our training and nutrition. Using a "smart scale" can help us get that data, but like a lot a lot of data, it's often misunderstood and misused.

I want to start by saying that if you know that looking at your weight and body fat every day will not be good for your mental/physical health, stop here. Trust me, I get it. Sometimes it's best to not have the numbers, which is why I don't look at my power or heart rate during races. Nothing good will come out of seeing that data in real time. With regard to body weight and body fat, you don't need a scale (or a power meter for that matter) to tell you whether or not you feel good and ultimately that's what's important. Losing weight won't improve your performance if you are missing workouts, feeling tired, getting sick or developing disordered eating habits. With that said, getting in a routine of stepping on the scale at a certain time every day as a matter of habit and having the additional data that smart scales provide may actually take the emotional issues out of the equation because the additional information demonstrates how incorrect it is to label any numbers or trends "good or "bad".

When I say "smart-scale", what I am referring to is a scale that reads (at a minimum) body weight and body fat %. Body fat % is estimated with electrical impedance and a number of user-inputs that may include height, sex and activity level. Certainly this is a crude and inaccurate way to estimate body fat % for many reasons but the more accurate methods (e.g. hydrostatic weighing) are extremely inconvenient and expensive. Body fat calipers can be more accurate for a well-trained user, but measurement varies greatly from user to user and they are not able to pick up small changes. Smart scales are inexpensive, convenient and relatively consistent provided the user-inputs remain the same and the conditions are relatively consistent each time the scale is used. Prices range anywhere from $30 to $200 for these scales. The higher priced scales are not necessarily more accurate, but they tend to have more features such as settings for multiple users, water % estimation, bone mass estimation and automatic uploads of data to phone apps via bluetooth or wifi. Judge for yourself whether or not these features are useful or not for you or not.

Naturally women tend to have a higher body fat % than men, but there is no formula to determine what is ideal or optimal for a given individual's performance or health. Nonetheless, body fat % is a much more meaningful measurement than Body Mass Index (BMI), which only takes height and weight into account.

Once you buy a scale, start using it. If you try it at different times of the day you will quickly realize how much the readings can vary, which is why it's important to take the measurement at the same time every day. If you work a 9-5 job, the best time is probably right after you get home but before you start your workout. If you're like me and your schedule is inconsistent, taking the reading first thing in the morning is probably best, despite the fact that there tend to be large fluctuations in hydration levels at that time. Next, start writing down the readings from each measurement on paper or in a spreadsheet (note: if you don't like doing that, it might be worth it to spring for a model that automatically uploads the data to an app!).

Taken alone, the numbers don't matter that much; the important thing is what the trend is. Once you have a week of data, you can start to dive in a little more deeply. Start by taking a 7-day rolling average of the values. For most people, body weight fluctuates by +/- 2 pounds or more throughout the day, which is mainly due to hydration. If you step on the scale and you are 2 pounds lighter than the day before, chances are you need to hydrate. A scale that estimates water % should tell you this, but even if you have a model that reads only weight and BF%, a sudden loss of weight and gain in BF% usually indicates dehydration.

Don't make too much out of individual readings, it's the trends that are significant

With at least 2 weeks of data, you can start to see what the trends are with your weight and body fat % by comparing this week's 7-day rolling averages to last week's 7-day rolling average or by graphing the data. For athletes looking to lose weight, a range of 0.5 to 1.0 pounds of weight loss per week on average should be the target. With this, you can already start to make adjustments to your diet. While it may seem nice to lose 2 pounds in a week, if you keep that trend up your energy will be low, your training will suffer and you can compromise your immunities. Not to mention, your metabolism may slow way down as your body goes into "survival mode". Certainly an average of 0.5 to 1 pound per week doesn't mean that each week you lose exactly the same amount, even when you are comparing 7-day rolling averages. But if you see more than 1 pound weight loss for more than 2 consecutive weeks, you should probably be taking in more energy if you don't want to get sick.

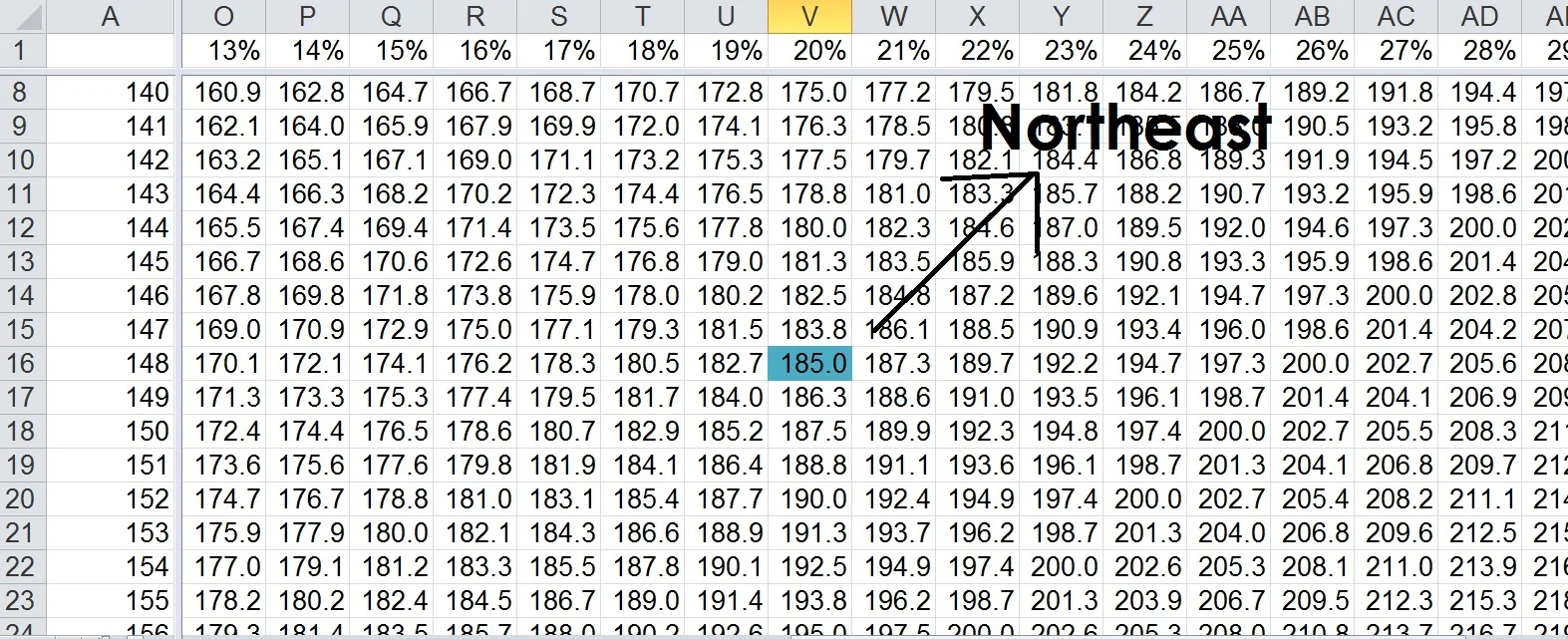

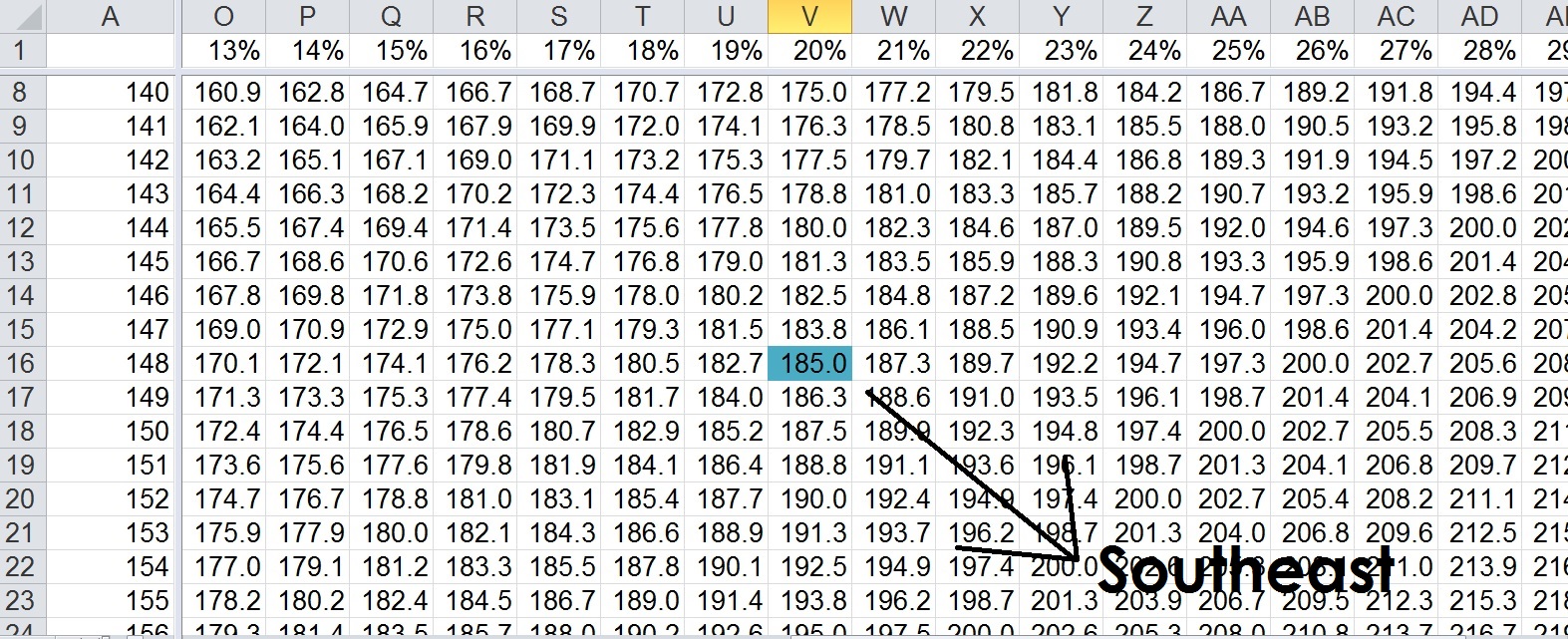

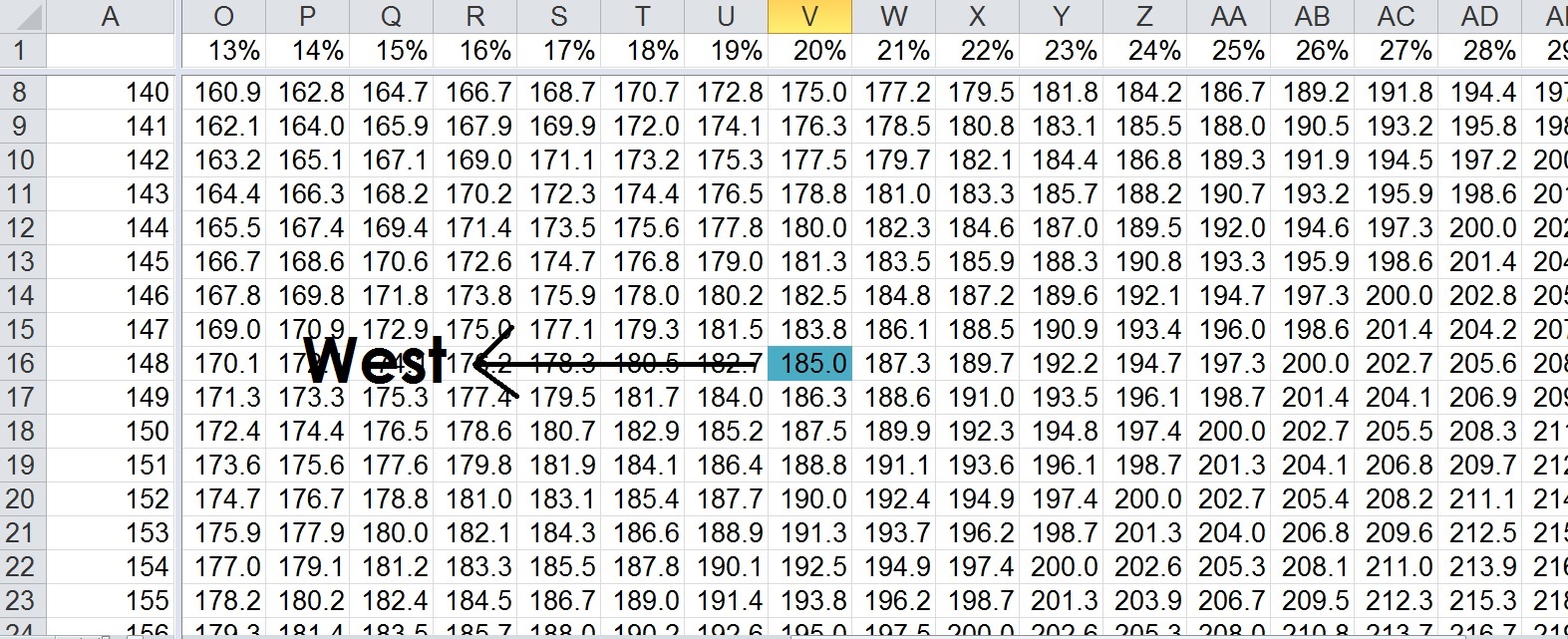

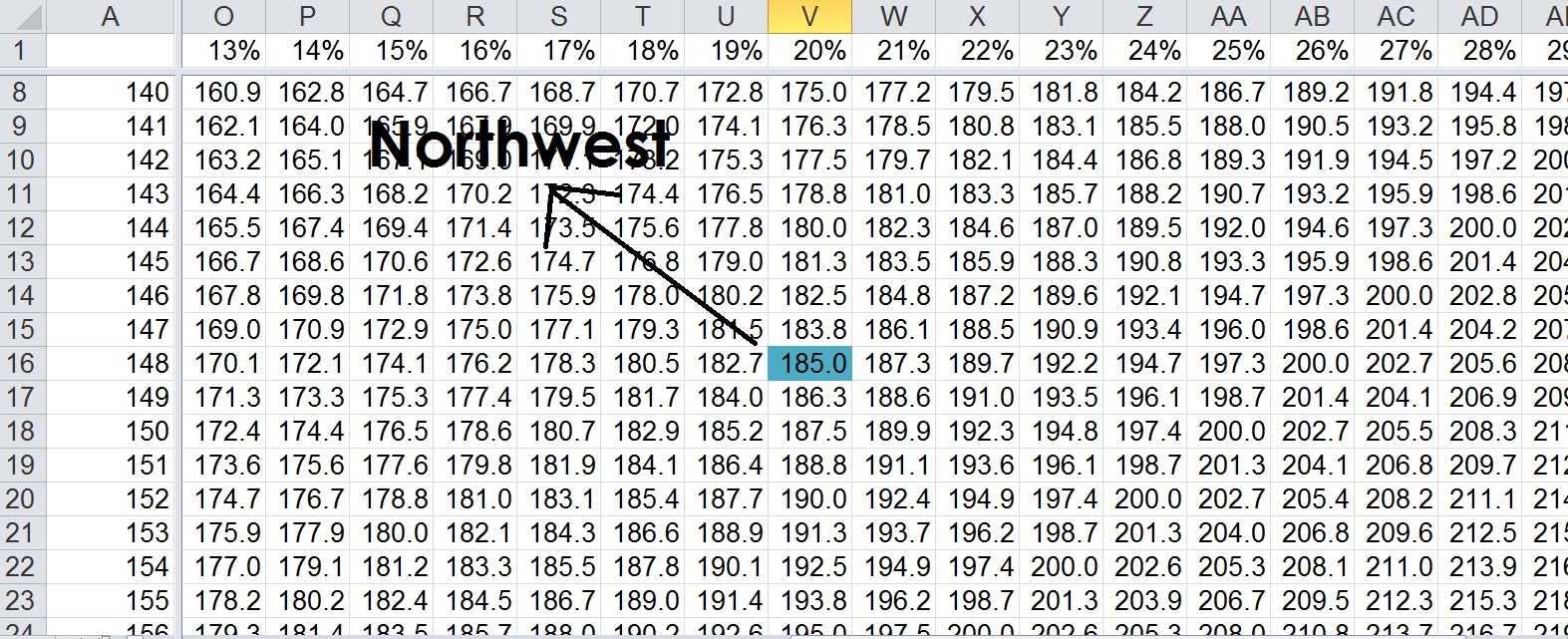

Let's look at an example here so we can see some actual numbers. A little basic math will tell you that if you are 20% body fat and you weigh 185 pounds, you have 32 pounds of body fat and 148 pounds of everything else (water, muscle, bone, organs, etc.) also referred to as lean body mass (LBM). Below, I made a table with LBM on the x-axis and Body Fat % on the y-axis:

A table with Body Fat % on the top row and Lean Body Mass on the Left Column. The values in the center represent Total Body Mass

The starting point of 185 pounds and 20% body fat is highlighted in the center. From this point, change may happen in any direction. Let's examine the possibilities:

North:

A northward trend on the table represents a loss of total body weight but a body fat % that remains the same. This means that weight loss is achieved by a loss of muscle or bone mass or dehydration, not from fat loss. From a performance standpoint, that's sort of like throwing the engine overboard to stop your boat from sinking. Now, if you're coming into cycling from a sport that requires much more upper body strength (e.g. baseball, weightlifting), northern movement may be wanted but for most of us it's undesirable. In order to curb northern movement, increase weight bearing exercises and on-the-bike strength work to retain muscle mass. Increasing daily calcium consumption as well as proper hydration are also important. It may also be helpful to increase protein intake.

Northeast:

A northeastern trend on the table represents an increase in body fat % and a decrease in lean body mass with total body mass remaining about the same. This is common when athletes stop training because of an illness, injury or simply to take a break at the end of their season. Total body weight may not change at first, but under the surface the body is losing muscle and gaining fat. From this chart, it may seem that northeastern movement is the worst case scenario, but a little bit of northeast movement at the end of the season may be unavoidable (because the alternative is to never take any time off). In order to avoid excessive northeastern movement however, athletes should reduce caloric intake (of carbohydrates and starches in particular), increase on/off the bike strength training and weight bearing activity and ensure an adequate intake of calcium and water to prevent dehydration and bone loss.

East:

An eastward trend represents an increase in body fat %, with lean body mass remaining constant and total body mass increasing. This means that you are consuming more calories than your body requires and that excess energy is being stored as body fat. An eastward trend usually happens when an training volume decreases but caloric intake remains the same (e.g. a recovery week). Despite the fact that most of us don't like to see the weight number on the scale go up, an eastern trend is most likely preferable to a northern or northeastern trend because lean body mass is not decreasing. To slow down or stop eastward movement, simple decrease intake. In particular, look to reduce sugar and starches first, since they are not required in the same quantities if training volume has decreased.

Southeast:

A southeast trend means that body fat, lean body mass and total body mass are all increasing, which is common after an endurance base period where volume was high but intensity was low. As intensity raises and volume decreases, muscle mass may increase but if caloric intake remains the same as it was in the base period, more energy is consumed than required and the excess is stored as body fat. Despite the fact that total body mass may be rising quickly, a southeast trend may not be as bad as it seems. If the increase in lean body mass is wanted but the increase in fat is not, the athlete simply needs to reduce their caloric intake. Shifting to a higher percentage of fat and protein and a lower percentage of carbohydrates may help curb appetite while still providing the necessary fuel for muscle growth. With that said, consuming carbohydrates and even sugar immediately before, during as well as immediately after high-intensity workouts is critical in order to ensure high performance.

South:

A southern trend means that lean body mass and total body mass are increasing but body fat % is remaining constant. When athletes not used to strength training first start up again, it's normal to put on a few pounds of muscle mass, especially in underdeveloped areas (typically arms, chest and back for cyclists). In some cases, southern movement means that an athlete is overdoing it in the gym. While some gain of muscle mass is accepted and even desirable, additional body weight is still weight that needs to be lugged up every hill, so in order to avoid excessive muscle gain, athletes should make sure that the strength training is cycling-specific and targeted to prevent injury and increase comfort and efficiency while riding. I am a firm believer in the importance of strength training, but ultimately you become a better bike rider by riding your bike, not by lifting weights.

Southwest:

Movement in the southwest direction means that lean body mass is increasing while body fat is decreasing, with total body mass remaining about the same . Southwestern movement is often seen when a high volume of strength training coincides with a high overall training volume; common for many cyclists in the late winter months. If weight loss is a goal, some athletes may be frustrated that despite all their hard work, the dial on the scale just doesn't seem to go down, but once again there is more going on beneath the surface than a weight measurement alone can measure. Indeed, if these athletes are patient, most will start to see southwestern movement become western movement once their strength training plateaus and/or their endurance training volume rises.

West:

A westward trend indicates that body fat and total body mass are decreasing while lean body mass remains about the same. In other words, weight loss is achieved completely through the loss of body fat. For cyclists, western movement typically occurs in periods where training volume is fairly high and intensity is moderate to high (e.g. a build period, a stage race or a training camp). Overall, total energy intake is less than expenditure so the body burns fat stores to make up the difference. Intensity is high enough to ensure that muscle mass remains constant. If body fat % is already low and the athlete does not wish to lose weight, they should look to consume more carbohydrates, preferably in the form of starchy vegetables and whole grains. It's also important to top off glycogen stores immediately before, during and immediately after high intensity exercise to ensure optimum performance.

Northwest:

A northwestern trend means that body fat, lean body mass and total body mass are all decreasing. It can be tempting to view any decrease in weight, especially a rapid one, as "good", but this is not necessarily the case. Northwestern movement typically happens when an athlete's training volume is high but that training does not include weight bearing exercise or strength work; not uncommon for many racers during their racing seasons. If they wish to curb the loss of lean body mass, these athletes should look to include some weight bearing exercise in their training regime and increase their protein intake. Like the northern and northeastern trends, adequate calcium and fluid intake are also critical to avoid dehydration and loss of bone mass.

So what are the take-homes here?

1. There is value in measuring weight and body fat every day, even if you aren't trying to lose weight. These readings can help you determine if you are dehydrated, losing muscle mass or bone mass, or if you need to make some tweaks to your nutrition or training. If you are trying to lose weight, taking a reading every day and looking at the trends is a heck of a lot easier than trying to estimate caloric intake and expenditure.

2. Your body is always changing. Those changes may be small but they are always happening. To be alive is to be changing. Having the instruments to see how (and how fast) you are changing can provide valuable insights and help you make adjustments to your training and nutrition in order to optimize your body for performance and health.

3. If weight loss is a goal, be patient. Just because the needle on the scale isn't moving (or isn't moving quickly enough for your liking), it doesn't mean your hard work and discipline isn't paying off. For example, southwestern movement may represent a loss of body fat and a gain of muscle mass, which from a performance standpoint may be the best of both worlds for many athletes. However, if you only measure total body mass, it may appear that nothing is happening. Likewise, the most rapid weight loss can occur when an athlete trends in the northwestern direction, but this movement may not be what is best for performance in the long run.

4. Changes in body composition aren't should never be regarded as "good" or "bad". This isn't "The Biggest Loser". The ultimate goal of losing [or gaining] weight, gaining [or losing] muscle mass is to improve performance and performance is a lot more than just power to weight ratio. In the long-term, performance requires good health and energy and most of all, consistency, which requires avoiding unnecessary illness and injury. No direction on the compass is purely positive or negative. Each direction tells a different story about how your body is affected by training and nutritional choices.

5. At one time or another, athletes will see movement in every direction. Trying to force indefinite movement in one direction is unsustainable. After all, if you walk far enough in any direction you will eventually come to the sea. Rather than trying to eliminate any movement in a direction that you deem undesirable, just try to reduce the amount of time and the speed that you move in that direction. For example, if you wish to lose weight, you will naturally want to increase the amount of time you spend moving west and decrease the amount of time they spend moving east. Unfortunately, the only way to eliminate eastern movement altogether is to never take time off and the only way to keep up western movement indefinitely is to keep training volume high indefinitely. Instead of trying to eliminate eastern movement, you can slow it down by staying active, making sure to include some strength training and by making some small nutritional changes (in this case, reducing sugars, starches and overall calories while increasing the percentage of calories coming from fat and protein).

Readers will note that I did not address many specifics on nutrition here except to say that nutrition should be periodized to coincide with training phases and goals, and this is on purpose. Stay tuned for one of my next blogs to be about that topic, but nutrition is way too big and multi-faceted to address in one single blog. Thanks for your patience!

Colin Sandberg is the owner and head coach of Backbone Performance, LLC. He is a Cat. 1 roadracer, a USA Cycling Level II coach and a UCI Director Sportif. He is also head coach at Young Medalists High Performance and race director for Team Young Medalists. If you have questions or comments, feel free to use the comments section or email us. Thanks for reading!