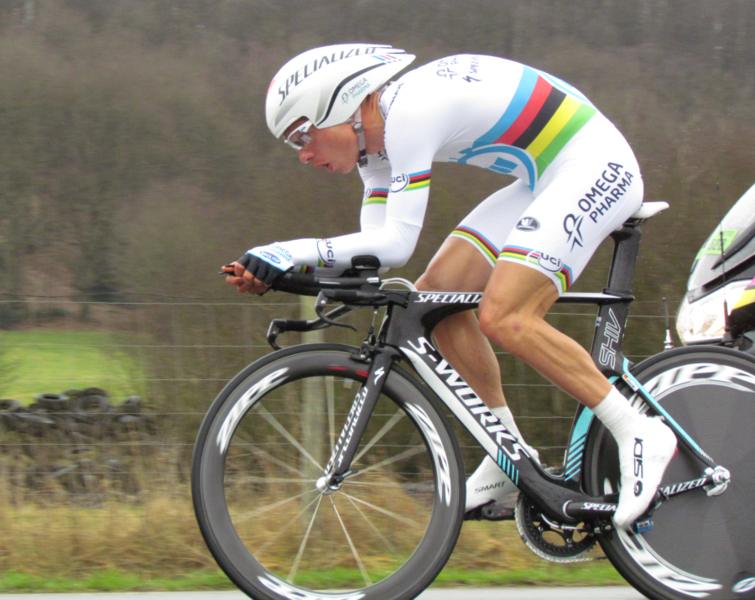

“In the midst of an ordinary training day, I try to remind myself that I’m preparing for the extraordinary”

- Shalene Flanagan, American 3000m, 5000m and 15k record holder, Olympic medalist, NYC Marathon winner

Shalene Flanagan winning the NYC Marathon in 2017. This was the first time an American woman had won the race in 40 years.

Cycling, though unique in many ways, is an endurance sport. Good old endurance rides, though not as “sexy” as a lot of other workouts are (or at least should be) the backbone of any cyclist’s training plan. Advocates of a polarized training approach recommend spending about 80% of rides or 90% of training volume at relatively low intensity (i.e. recovery and endurance). Unfortunately, many riders treat these rides more like “filler” workouts than giving them the respect they deserve. There are many reasons for this; some find endurance rides boring, some find them difficult to complete when it’s dark, cold, wet or snowy outdoors. Many athletes, when pressed for time, prioritize their high intensity workouts. Some choose to complete their endurance rides with a group, only to get sucked into prolonged, but unstructured periods of high intensity as well as long periods of coasting and soft-pedaling, resulting in workouts that take a lot of time but are limited in their training value. Others, even when riding by themselves, either lack the discipline to keep their intensity low or have a “no pain, no gain” attitude towards training, leading them to ride moderately hard all the time and ultimately, not hard enough on their hard days.

In previous articles, I’ve explained the importance of endurance rides and how to complete them properly. I’m not going to rehash all of that again here, but as a reminder, the 2 most important rules for endurance rides are 1. Keep your heart rate in zones 1 and 2 (under 83% of threshold HR or about 75% of max HR) and 2. Minimize coasting time. These are simple rules, but I am continually surprised at how difficult it seems to be for so many athletes to execute them properly. The following is a list of ways that athletes can add value to their endurance and recovery rides, make them more enjoyable and easier to accomplish properly, given the real world constraints we all face:

1. Mix up the cadence. Most cycling events require power and efficiency at a range of cadences. While this range may be much tighter in flat time trials than in Criteriums and Cyclocross races, most riders can benefit from widening their “cadence comfort zone”. Making a conscious effort to increase cadence at least one gear above where you would normally ride will benefit pedaling efficiency. If you’re riding indoors using a VR program such as Zwift, it can be helpful to ride a rolling or hilly course that forces you to shift and ride at a wider range of rpm, even when your power remains relatively constant. Even those riding “dumb trainers” should consider changing up their cadence every 5 minutes (e.g. 5 min at 85 rpm, 5 min at 90 rpm, 5 min @ 95 rpm, 5 min @ 100 rpm…). In addition to expanding your range of efficiency, changing things up every few minutes also serves to make these indoor rides less mind-numbingly boring. Some riders might consider riding a fixed gear bike outdoors over rolling terrain, which will improve muscular strength on the uphills, leg speed and efficiency on the downhills and as a side benefit, keep your primary bike clean.

VR apps such as Zwift can make indoor riding a lot less boring, but most riders should still reduce their volume if riding endurance rides indoors. It’s also important not to get sucked into the competitive aspect if the goal is Endurance. Save the intensity for your hard days!

2. Cut the volume down when riding indoors. I don’t know about you, but a 3 hour outdoor endurance ride is something I usually look forward to. A 3 hour indoor endurance ride, on the other hand, is something I usually dread. Hence, there is “The 2/3 rule”, which basically states that you can cut out 1/3 of the volume if you’re riding indoors because there is little or no coasting or stopping. In an age when most serious cyclists are using power meters, we now have actual data to back this up. When planning workouts, I assume an intensity factor (IF) of 0.60 when riding endurance outdoors, which means that a 3 hour endurance ride would produce a Training Stress Score (TSS) of 108. Indoors however, I’ve found that most riders will maintain an IF closer to 0.70, which means that they will rack up a TSS of 108 in just over 2 hours (2 hours and 11 minutes to be exact). With that said, I still prefer for riders to complete endurance rides outdoors when possible, I just know that in the real world it is not always possible, be it due to daylight, weather, or road/trail conditions.

3. Mix up the modality. For example, if it’s cold outside you could spend the first half of your ride outdoors and the second half indoors. If there’s snow and/or ice on the roads and outdoor riding is unsafe you could spend the first half skiing or snow-shoeing and the second half on the bike. If you’re getting bored with your fixed wheel indoor trainer, you could spend the first half of the ride on the trainer and the second half on the rollers (which will have the added benefit of improving balance and concentration).

Including rollers in your indoor training regimen can help with leg speed, balance and concentration. If you’re Eddy Merckx, it might also be a the perfect time to have a talk with your daughter…

4. Slow it down. One of the worst parts of riding outside on a bitterly cold day is the “wind chill”. 20 degrees might not feel too bad at first if you’re properly dressed, but riding down a descent at 40 mph when it’s 20 degrees can chill you to the bone. Though most of us are used to looking for ways we can ride faster, it may be helpful on those cold days to have the opposite mentality. One way to do that is to ride a mountain bike, cyclocross bike or fat bike in the woods. Your speed will be lower and the trees can give you some added shelter from the wind. If you still want to ride on the road, consider outfitting your bike with fenders, thorn proof tubes and thick tires. It may feel like you’re riding in wet cement but the wind won’t be as bothersome (and you’re less likely to have to change a flat tire on a cold day). Many opt to ride a separate “winter bike”, which will save the primary bike from being subjected to the harsh winter conditions. Note: it’s important to be properly fitted on each of your bikes by a professional fitter. Even if you carefully match saddle height, setback, reach and drop, the fit will be slightly different.

5. Work on “body management”. When examining workout files from endurance rides, a couple metrics I look at are Efficiency Factor (EF) and Pw:HR. EF is simply Normalized Power/Average Heart Rate and Pw: HR compares EF in the first half of the ride to EF in the second half of the ride. An athlete who is fit, efficient and does a good job of body management (i.e. eating, drinking, staying relaxed, staying cool, avoiding excessive muscular fatigue, etc.) will have a lower Pw:HR. Conversely, athletes who are inefficient, fail to consume adequate fluid and Calories, waste a lot of energy or overheat during a ride will have a high degree of aerobic decoupling, meaning that they will see their heart rate drift higher and higher even at a consistent power output OR see their power drift downward even at a consistent heart rate. Overall, EF and Pw:HR on endurance rides should go down as you get more fit and efficient, but these improvements are equally about body management. To use a car metaphor, even if you drive a Ferrari, you have to change the oil, change the tires and put gas in the tank.

Endurance rides are a good time to work on cornering, descending and other skills, but you should practice the skills that are in line with your level of ability and confidence

6. Work on your bike handling skills. Low intensity rides are perhaps the best time to work on the bike handling skills that many riders neglect. Try riding with your hands off the bars. Try taking an energy bar out of your back pocket and unwrapping it while riding. Try removing your vest, gloves, booties or leg warmers, putting them in your back pocket, and putting them back on while riding. To be clear, riders should practice skills that match their experience and ability. Safety should be the first priority. For example, beginner riders might want to practice riding out of the saddle comfortably on the uphills before they graduate to removing their base layer on a descent or cooking an omelet on the rollers. When cornering and descending, all riders should practice choosing lines, weighting their outside leg, sighting the turn and other cornering techniques. If you’re riding off road, there are limitless possibilities for skill work and because endurance rides will be done at lower speeds, you won’t have the added momentum that can sometimes make up for poor technique.

7. Work on your pedaling efficiency. I mentioned increasing cadence in order to improve mechanical efficiency in #1, but even when you’re not doing anything specific to work on your pedaling efficiency, simple awareness may help. If you’re riding with a dual-sided power meter, it could be a good time to check your L/R power split and try to ride as close as possible to 50/50 (note: this is particularly important for riders with significant leg length or strength discrepancies). Some power meters are also capable of producing real-time efficiency metrics such as pedal smoothness, torque effectiveness, power phase and platform center offset. If you feel pretty confident about your efficiency metrics under normal conditions, there are a few “handicaps” you can give yourself, such as riding in the drops or aero bars. Doing so can help you improve flexibility, hip flexor and core strength as well as get you more comfortable riding in the positions that you will eventually have to race in.

8. Try depletion rides. Though it would be wrong to suppose that a 1 or 2 hour endurance ride isn’t even worth doing, most riders will spend the first 15-30 minutes of their ride burning a high percentage of muscle glycogen, which means that most of the gains in metabolic efficiency (i.e. burning a higher percentage of fat) will come later in the ride. There is however, a way to “shortcut” this process by beginning the ride with depleted glycogen stores. Typically this is done by riding first thing in the morning (i.e. before breakfast), but it can also be done in the late afternoon or early evening when you haven’t eaten in 6+ hours. A word of warning though: depletion rides can be a lot more painful than regular endurance rides and depletion rides over 2 hours long are not recommended except for elite and professional cyclists.

You have to get to work one way of another. Why not use it as training?

9. Commute. If you are able to ride your bike to and from work, it’s a relatively easy way to tack on some extra miles. Most commuters will have a tough time working in structured intervals during their commutes, but riding recovery and endurance rides is usually possible. A 45-90 minute commute may not seem like it’s that long, but if you multiply by 2 times a day and 5 days a week, you’ve already got yourself 7.5-15 hours per week! Some riders may wish to do depletion rides (see above) on certain days by eating breakfast after they arrive at work and refraining from eating in the afternoon until they arrive at home. If you do rely on commutes as your main source of endurance time however, make sure that you choose safe routes that minimize coasting and soft-pedaling time and allow yourself adequate time to get to work and get cleaned up so you don’t end up having to go harder than you wanted just so you can make it there on time. Finally, make sure you have another form of transportation available in case it’s unsafe to ride or you just plain need a day off.

10. Listen to podcasts and audiobooks. OK, I always feel like I need to have a legal disclaimer with this one so before I go any further, I will say that I do not recommend riding with headphones if it is illegal in your state/city/township or if you just don’t feel safe doing so. In other words, ride with headphones at your own risk. That said, if you are OK with it, listening to a good book or podcast can make a long endurance ride a LOT less boring and on top of that you will be educating your mind and training your body at the same time. Personally, I like to listen to music during harder training sessions but on those long endurance days, I love nothing more than listening to a good book or podcast. As someone who never seems to find time to read as much as I’d like, this has been life-changing, though admittedly some books are better to listen to than others on rides (pro tip: think Stephen King, not James Joyce) By the way, this blog is brought to you by Audible (just kidding, but Audible… if you’re out there, call me!)

On a final note, I want to loop back to the beginning and remind readers that these are tips to help make your endurance rides more achievable, valuable and fun, but it needs to be said that they can also be misconstrued in ways that actually lead to lower-quality endurance rides (which more often than not means riding too hard). If you increase your cadence, make sure that your heart rate remains low even if you have to ride at a lower power. If you cut your volume down indoors, it doesn’t mean you should bring the intensity up. Increases in IF will occur because there is less time stopped or soft pedaling, not because the actual riding intensity is higher. If you supplement your endurance work with cross training, it is true that heart rate zones can be different in different sports, but if the goal is endurance, keep it at endurance HR. If you decide to ride on a mountain bike, fat bike or cross bike in the winter, it’s understandable that the terrain might include a few more power spikes but it’s important to select routes that don’t require prolonged periods of high intensity just to stay on the bike. Lastly, although you may feel less hungry on a long endurance ride than a long high-intensity ride, you still need to eat and drink. If you’re looking to lose weight, do it through consistent training and incremental and sustainable modifications to your off-the-bike nutrition.

Simply put, whatever methods and tricks you use to get through your endurance rides, know the difference between endurance and “endurance”. One is the foundation of your fitness and the key to sustainable improvement. The other is just gets in the way of making long term gains… what’s the word I’m looking for? Oh yeah, junk. That’s it.

Colin Sandberg is the owner and head coach of Backbone Performance, LLC. He is a Cat. 1 road racer, a USA Cycling Level II coach and a UCI Director Sportif. If you have questions or comments, feel free to use the comments section or email us. Thanks for reading!